|

|

|

When the Miners Said Goodbye Forever

(by Mike Havrischak, The Valley Gazette, April 1973)

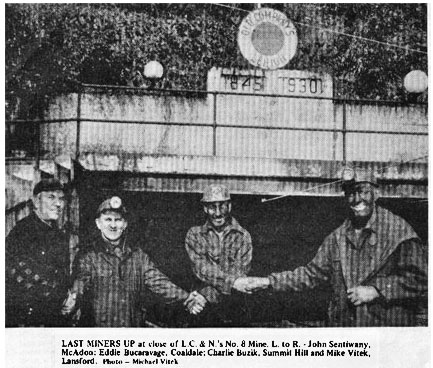

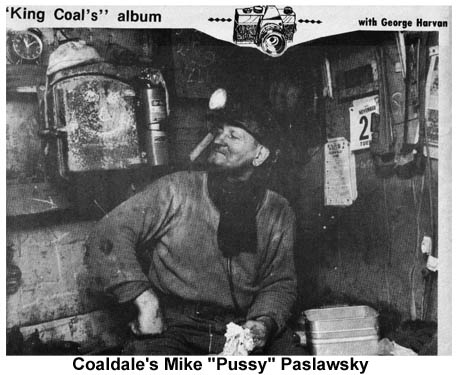

A livelihood for over 150 years was to virtually disappear as “King Coal” breathed his last. Years before, such men as Casey Gildea in a special edition of his Coaldale Observer in 1954 reported what the future held. He reported what C. Millard Dodson, the newly-elected president of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, said. Dodson stated, “There’s not a wheel turning in the Panther Valley today. The wheels may never turn again, but if they do turn, there will be fewer wheels in motion than heretofore, and next year, and the year after next, there will be fewer and still fewer wheels in motion.” It was evident that the time was at hand for the Panther Valley to start seeking a new economic base. After overcoming a slump in 1954, deep-mining in the Panther Valley resuled and prosperity was back for a few years more, but on borrowed time. Efforts to keep mining alive were being hampered by the increased costs of digging coal and its preparation. In addition coal was facing competition from other fuels such as oil and gas. Elsewhere, others had years before ceasing their operations. Then one the Valley’s some 5,000 miners were given notices that the mines were to be shut down. Shut-downs were nothing new to Valley mining families who had before experienced them. However, this one was to be different. Once shut down, the mines were never to re-open. On the last day the shifts came to work as usual. Coal was being loaded from the chutes and hoisted to the breaker up on the surface. Empty coal cars loaded with the miners’ tools were also being sent up the shafts. After completing their last shift the miners gathered their tools to take home. They left behind the dark underground passages as they walked toward the shafts for their last ride up. Once on the surface they proceeded to the lamphouse and then into the wash-shanty for the last time. After taking a shower the miners gathered their clothes and personal belongings from their clothes hook and basket. Friends bid each other farewell, since some miners were from outside the Panther Valley and probably would not be seen again for some time. A short walk to their autos in the parking lot and a last look backward, and it was over. Those years of working in the mines! What the future would hold was a mystery. Rumors would occasionally spread that the mines would shortly be re-opened. It was evident they would not when salvage crews were dismantling the huge breakers for equipment and scrap metal. Some men knew they were not to return to work in the mines. The best years of many men were already past, so retirement would be their solution rather than seeking other employment. Careers, some starting over 50 years ago in mining, ended. Some men started as breaker boys picking slate, or as door-boys inside the mines—many before the age of automation when hand tools, torch lights, black powder, and mules were commonly used. While still others started later when pneumatic tools, electric lights, and permissible explosives were used. Many miners never had the opportunity to complete their high school educations because they were of greater importance working in the mines as breadwinners for their families. The Panther Valley’s deep mines today sit filled with water, but someday when new scientific methods of extracting coal are practiced these mines may be re-opened. Each year less and less of the Valley’s veteran miners are around. Strip mining still recovers the Valley’s coal, while stories of our deep-mining heritage are all that remain of a once-vast industry in the Panther Valley. |

Some miners had realized that they were never to return to their working places. Like a time capsule for future generations, they left signs for others to read. One miner enclosed a paper with his name bearing a message inside two jars at his working place. Others wrote their names and date on the timbers. Messages like “Good-bye boys” and “So-long” were left. One miner remembers a message when someone had written in Slavonic which translated meant “good-bye forever!” This last message for many of the Panther Valley’s miners was to come true in time.

Some miners had realized that they were never to return to their working places. Like a time capsule for future generations, they left signs for others to read. One miner enclosed a paper with his name bearing a message inside two jars at his working place. Others wrote their names and date on the timbers. Messages like “Good-bye boys” and “So-long” were left. One miner remembers a message when someone had written in Slavonic which translated meant “good-bye forever!” This last message for many of the Panther Valley’s miners was to come true in time. Other men were still in their prime or only middle-aged, so they still had to work for a livelihood. Unemployment benefits would temporarily help their families until another job was found. Anthra-silicosis benefits would alleviate the economic plight of other families. Some mothers went to work in local clothing factories to supplement the decreased family income. New local industries would eventually provide men with additional jobs, while many were forced to commute or move away to other industrial areas.

Other men were still in their prime or only middle-aged, so they still had to work for a livelihood. Unemployment benefits would temporarily help their families until another job was found. Anthra-silicosis benefits would alleviate the economic plight of other families. Some mothers went to work in local clothing factories to supplement the decreased family income. New local industries would eventually provide men with additional jobs, while many were forced to commute or move away to other industrial areas.