EXCERPTS:

-- More than 130 years later, the legacy of the Molly Maguires is still evolving, and remains contentious.

--James Roarity (Note: of Coaldale), who was convicted of killing policeman Benjamin Yost, said before his hanging in 1877: "I am going to die an innocent man."

-- To some, they were nothing more than thugs who ruthlessly killed the mine bosses who employed them. Others, meanwhile, have crowned them the patron saints of the modern labor movement who used anarchy and class warfare to fight against harsh working conditions.

FULL ARTICLE:

To some, they were nothing more than thugs who ruthlessly killed the mine bosses who employed them.

Others, meanwhile, have crowned them the patron saints of the modern labor movement who used anarchy and class warfare to fight against harsh working conditions.

Who were the Molly Maguires and what, if anything, is their legacy?

Both sides can agree on the basic facts of the case.

The group that came to be called the Molly Maguires first drew public notice in Jim Thorpe, Pottsville and other towns in the coal mining regions in the 1850s. Twenty years later, 20 so-called members of the Molly Maguires would be found guilty of plotting the deaths of 16 mine officials and policemen. The men would come to be immortalized by their executions, in part because many proclaimed their innocence until the very end.

For example, James Roarity, who was convicted of killing policeman Benjamin Yost, said before his hanging in 1877: "I am going to die an innocent man."

John "Black Jack" Kehoe, the alleged leader of the Mollies, made a similar declaration about his conviction for the murder of mine foreman Frank W. Langdon. While standing on the scaffold before his execution in 1878, Kehoe said, "I am not guilty of the murder of Langdon; I never saw the crime committed; I know nothing of it."

The convicted men were coal miners, many of whom had been born in Ireland. They were given the name Molly Maguires by the newspapers and police of the era, who said it was a secret society that was behind a wave of violence targeting mines. It's not clear how many members the group had. Another organization by the same name had long roots in Ireland.

The group emerged at a time of national unrest among workers, particularly those laboring in mines. Wages were at the heart of the disagreements between workers and owners. Salaries typically depended on the price of coal, so when coal prices fell, wages fell too.

The workers wanted owners to adopt an eight-hour workday. Workers also faced hazards in the mines every day, chief among them "black lung" or miner's asthma. Miners wanted health care coverage in the form of company-run hospitals.

A spate of violence that embroiled Carbon and Schuylkill counties in the mid-1870s followed a failed strike organized by the Workingmen's Benevolent Association. That union formed in 1868 in St. Clair, Schuylkill County. The six-month strike, which had successfully unified thousands of workers across several counties, ended bitterly in mid-1875 when the workers gave up and returned to the mines.

Franklin B. Gowen, head of the Reading Railroad, which had major interests in coal, hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to infiltrate the Mollies following a series of suspicious incidents, including fires at mines. The testimony of a Pinkerton detective, James McParlan, was decisive in convicting the men.

The trials of the Molly Maguires captivated Jim Thorpe, Pottsville and the surrounding areas from 1876 to 1879, when the last coal miner was executed. Newspapers from New York and other areas of the country sent reporters to cover the trials.

"Day of the Rope'

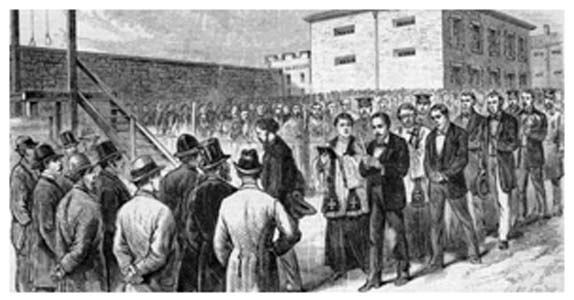

The mania came to a head June 21, 1877, or "The Day of the Rope," as it's still known in Schuylkill County. The moniker refers to nooses used to execute six miners in Pottsville in the first round of executions. Another four men were executed the same day in Jim Thorpe, then known as Mauch Chunk. By 1879, 20 mineworkers were executed.

More than 130 years later, the legacy of the Molly Maguires is still evolving, and remains contentious.

To Leo Ward, president of the Historical Society of Schuylkill County, the Molly Maguires have nothing to do with the history of organized labor. Ward said given its predilection for violence, the group contributed nothing positive.

"I don't think they were trying to play a prominent role in history," Ward said.

There is some veracity to what he says. The convicted men did not form an official union. It's even debated whether there was a formal group called the Molly Maguires, or whether the men were simply members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, an Irish fraternal organization. Local union officials at the time, including John Siney of the WBA in St. Clair, took pains to differentiate themselves from the Molly Maguires. That's because the union opposed violence.

While it's likely some of the Molly Maguires were not guilty of murder, they probably participated in other acts of violence, including sabotage. In their view, violence could accomplish what the union had failed to do.

Jimmy "Powderkeg" Kerrigan, a Molly Maguire from Tamaqua who became an informer, was quoted in an undated issue of The Mauch Chunk Democrat as saying, "The notion is that it is to protect the workingmen, but really they are all of the most hardened villains."

Most experts say the Mollies were not violent for the sake of violence. Instead, they were motivated by the harsh working conditions miners faced in Northeast Pennsylvania. And the groups that went after them -- the mine bosses, the government, the coal mine police -- targeted them to squelch early labor unions, these experts believe.

"The problem with dissociating the Molly Maguires entirely from labor activism was that it robbed them of any motive other than revenge or bloodlust," wrote Kevin Kenny in his 1998 book, "Making Sense of the Molly Maguires."

Source: http://articles.mcall.com/2007-03-04/features/3712890_1_coal-mining-regions-molly-maguires-schuylkill-county/2