When the coal mine breaker whistle blew, dogs howled and children put their fingers in their ears to shut out the shrill and offensive sound. But when the whistle blew at any time other then the usual 5 a.m., which signaled the start of the workday, there was cause for alarm.

The whistle's grim cry for assistance sounded shortly after noon Monday, Sept. 27, 1915. Eleven miners had become entombed in Foster's Tunnel south of Coaldale Hospital. What followed was one of the most suspenseful weeks in Panther Valley history. The tunnel became the focal point of one of this area's most extraordinary mine disasters and rescue efforts. But no one could have anticipated how the seeming tragedy would end.

All able-bodied men who were not working, local doctors, off-duty nurses, first-aid teams and the local ambulance corps reported to the mine. Nearby, the Nesquehoning undertaker's hearse maintained its ominous vigil.

The prospects for the miners were not good. Tappings from the men had fallen silent, and rescuers feared the worst.

Fortunately, two of the 11 trapped men, William `Kaska Bill` Watkins of Bloomingdale, a Panther Valley patch town, and George `Gint` Hollywood of Coaldale, followed running water and were found by rescuers that day.

Another trapped miner, William `Kelly` Watkins, the son of Thomas Watkins of Mill Street in Nesquehoning, walked unaided from the tunnel and went directly to a telephone to call his wife. `Is that you, Sadie?` he cried. `Thank God, I'm safe. I'll be home in 15 minutes!`

Foster's Tunnel had been driven southward into Sharpe Mountain as a water-level tunnel. When the tunnel reached the Mammoth vein, miners followed the large vein west toward Tamaqua and east toward Lansford.

It was in this `east bottom split` of the tunnel that the roof collapsed, trapping the men behind a huge wall of debris.

Because Foster's Tunnel was at the lowest point of the workings, it also drained water to the outside from the upper levels and the tunnel itself.

The spill blocked drainage and water began to flood the tunnel behind it. The miners now faced triple jeopardy: entrapment, rising floodwater and the formation of deadly gases known as `black damp.`

That three men had survived spurred the rescue parties to dig furiously. By that evening, the men had cleared 56 feet of the gangway but there was no sign of the eight others.

On Thursday morning, Sept. 30, rescue parties stopped digging and listened for tappings; tapping is the miners' traditional way of letting rescuers know they still are alive. There were none, but the digging continued.

By this time, 126 carloads of debris had been removed; however, there was still no sign of life. The Tamaqua Evening Courier headline on Friday, Oct. 1, read, `Hope of Recovering Men Entombed in Foster's Tunnel is Abandoned.`

The rescue workers had encountered deadly black damp during their frenzied efforts and had to wait until the gas cleared before resuming their work. When news of the gas reached the surface, the father of one of the miners was quoted as saying, `Their chances are one in a thousand!`

During the afternoon of Sunday, Oct. 3, tunnel foreman John Humphries climbed on a makeshift raft and floated into the mine on water that partly filled the gangway. Shouting as he went, Humphries was elated when he received an answer to his calls.

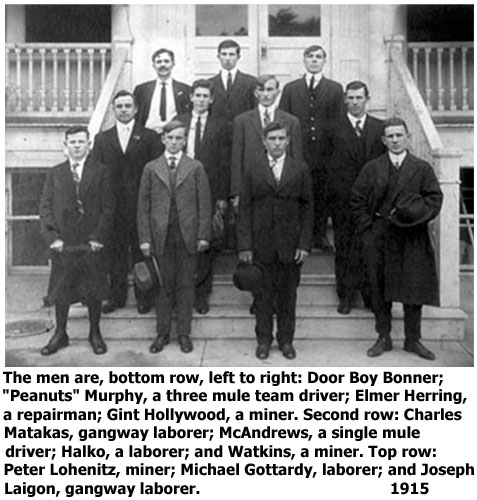

The foreman found the eight miners huddled together in Chute No. 27, miraculously still alive after being entombed for almost a week.

The Tamaqua Evening Courier carried the welcome news on Monday, Oct. 4, quoting a rescue worker who brought the news to the surface. `They're alive! They're all alive! We found them!` he screamed in joy.

The men were weak and exhausted after their ordeal, but none was seriously injured. When their food had run out, the hungry men had eaten the `sunshine,` the wax that fueled the lights on their helmets and had drunk the alum-tainted water from the mine.

The crowd that had gathered around the tunnel portal bowed heads in a moment of thankful prayer and then let loose a tremendous cheer that echoed off the mountainsides surrounding the valley.

The crowd pressed forward as the men were carried from the tunnel.

Everyone wanted to see the miracle that had occurred. The half-starved, sunken-eyed men waved weakly from their stretchers as they were loaded into ambulances.

The crowd slowly dispersed. Many went quietly to their churches to offer prayers of thanksgiving.

The Coaldale Observer aptly reported, `They survived hardships which cannot be pictured by tongue or pen,` on that day, Oct. 4, 1915.

Accidents such as this were not unusual but few had such a happy ending.

Georgie Pauff is a Nesquehoning author and president of the Nesquehoning Historical Society.

Source: http://articles.mcall.com/2000-03-09/news/3289906_1_miners-rescue-foster-s-tunnel