Sunday, August 31, 2008

Dr. Jim Dougherty says he had one of the most exciting jobs in Washington.

Dougherty was the director of the media program for the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). When you watch a program on PBS that "was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities," Dougherty's fingerprints were most likely all over it. His distinguished career with that federal agency spanned more than two decades and four presidential administrations.

"It was the most highly pressurized job in the Endowment," he says.

Scholarship has defined Dougherty's life. Holding a Ph.D. in modern European and U.S. history from the University of Maryland, Dougherty is a published author. He taught part-time at the university level while working at NEH and most recently taught history, political science and economics at The O'Neal School in Southern Pines, where students affectionately knew him as "Dr. D."

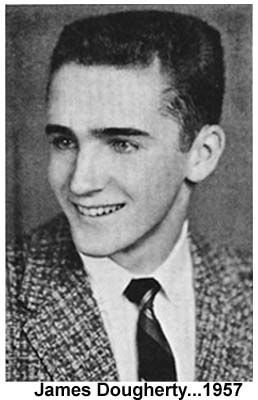

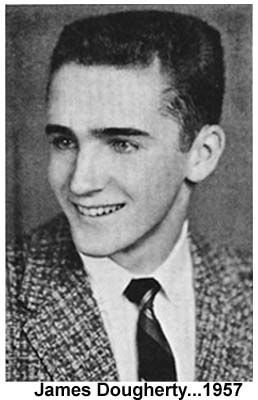

Dougherty's journey from the crowded halls of Washington to the friendly fairways of Pinehurst really begins in the coal-mining region of Pennsylvania. He hails from the tough town of Coaldale, in the eastern part of the state some 50 miles south of Scranton.

The son of the prominent town doctor, Dougherty grew up in a strong Irish Catholic family and attended Catholic grade school and public high school. While Coaldale is now merely a shell of the booming mining center it was in the mid-20th century, Dougherty says its "physical" character inspired all the kids who lived there.

"Everyone aspired to be the next great athlete," he says, adding that he played four sports. "Six thousand people would turn out for football games. I loved it."

Dougherty also found inspiration in his high school faculty. Part of a graduating class of 50, Dougherty says he benefited from having teachers who all had master's degrees. He believes the school did a lot to help kids get out of Coaldale.

"The public school saved hundreds of kids who went through it," he says.

Always Challenging Students

Dougherty was one of those kids. He enrolled in the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Notre Dame for his undergraduate work, a background he calls "just crucial" to his career.

While he was drawn to South Bend for all of the athletic reasons one would expect -- though he is quick to point out the football program was not up to snuff during his time there -- he was blown away by the philosophical experience at the school.

Notre Dame, like many other Catholic schools, Dougherty says, challenges students to constantly ask "why?" while exploring the history of ideas. Anyone sitting in on one of Dougherty's classes will notice that he tries to get all of his students talking and asking questions, even if they haven't formulated a clear opinion on the subject.

Dougherty describes Notre Dame in the late '50s as "West Point or Annapolis without the uniforms," a reference to the strict rules and regulations at the school. Priests were stationed on each hall as prefects to watch out for any shenanigans. At 11 o'clock each night, the power went out in the dorms and students literally couldn't turn on the lights.

Despite those few quirks, Dougherty lives, breathes and bleeds navy, green, and gold. His dark-green Mazda Miata convertible proudly displays a vanity plate reading, "DOC ND61." He even holds season tickets to Irish football.

Close friend and fellow ND alum Dr. John Dempsey, president of Sandhills Community College, jokes about Dougherty's passion for the Irish.

"Jim seems like such a mild-mannered and soft-spoken gentleman, which he is," Dempsey says. "But when he sees a coaching mistake while watching Notre Dame, he just goes crazy!"

Because a serious leg injury forced him to return home to Pennsylvania for a semester, Dougherty graduated in four and a half years, class of 1962, allowing him to enjoy an extra football season.

Publish or Perish

After graduating from Notre Dame, Dougherty continued his education at the University of Maryland. While pursuing his doctorate, he worked as a teaching assistant in the history department and -- surprise -- served as an athletic tutor for the Terrapins' football team.

Schooled by some of the most distinguished historians of the time, Dougherty was instilled with the motto of "publish or perish" -- that is, finding a unique dissertation topic to write about.

"Everything was geared toward picking a dissertation topic that was new and publishable," he says. "That's something I still believe in."

Dougherty's work, "The Politics of Wartime Aid: American Economic Assistance to France and French Northwest Africa 1940-1946," was published. A chapter from that book also appeared in "Cahiers d'Etudes Africaines," a French historical journal.

Dougherty was at Maryland for most of the tumultuous 1960s, teaching for a year after completing his dissertation. Being part of the campus protests and civil unrest of the time influenced him heavily and led him to his career in government.

"I was always on the periphery," he says, pointing out that his parents were Eisenhower Republicans and that he considers himself more of a product of the '50s than the '60s. "But it shaped my thinking in an invaluable way. People who weren't in that situation missed a whole lot."

Sustaining Democracy

After a three-year stint in academic editing while teaching classes part-time, Dougherty landed at the NEH during the Carter administration. He initially worked as a program officer in the public programs department at the Endowment, working with national organizations like the NAACP and labor unions to enrich educational programs with the humanities.

In the early 1980s, he became director of media programs, which became the focal point of the Public Programs Department. During his 15-year tenure, he and his staff were charged with overseeing the production of hundreds of educational documentaries and dramas, a task he describes as "enormous."

"It was a constant battle to get the program funded," Dougherty says, adding that his biggest resistance came from Lynne Cheney, the wife of the future vice president, when she chaired NEH. Cheney, like many conservatives, argued that film, especially drama, was a superficial form of scholarship. While both sides, including every NEH chairman Dougherty worked under, worried and complained about bias, conservatives were increasingly suspicious that liberals dominated both NEH and PBS.

While Dougherty understood Cheney's position that dramas were more of a creative art, he argues that they are "absolutely essential" to get certain fields across to the public. He says, for example, that a documentary on literature is extremely tedious and much less memorable than a drama on the same subject.

Despite the political push and pull of the time, Dougherty found a way to succeed during the conservative Reagan/Bush years and the more liberal Clinton administration. His projects made a significant contribution to public understanding of issues.

In addition to Barbara Kopple's Oscar-winning "American Dream," perhaps Dougherty's greatest achievement was the production of "The Civil War," a nine-part documentary created by Ken Burns that garnered over 40 million viewers in 1990 and set a ratings record for PBS. Dougherty was also responsible for the creation of a series on American presidents from Teddy Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan.

Dougherty considers understanding of the humanities as vital to American society.

"If a democratic society is to endure, it demands an informed electorate that knows culture, literature, history, and so on," he says. "Democracy is sustained through the humanities."

O'Neal and Beyond

Dougherty and his wife Pam, who worked with the U.S. Department of Commerce in Washington, were married in 1998 at the Village Chapel in Pinehurst. Both avid golfers, they long viewed Pinehurst as the place they wanted to retire.

Dougherty considered teaching at the university level again, but ultimately decided on O'Neal after conversations with outgoing Headmaster Gardener Dodd and Alice Robbins, head of the Upper School. During his time at the school, Dougherty passionately immersed himself in all aspects of student life and quickly became a favorite of students and faculty alike.

"He commanded the respect of students and colleagues," says Jay St. John, who was headmaster at O'Neal during Dougherty's tenure. "He's an incredibly humble guy who really put students first in my book. I've worked with a lot of people, but Jim Dougherty is definitely at the top of the list."

Eric Subin, one of Dougherty's former students at O'Neal and a graduate of Emory University, who is attending law school at the University of Denver, says Dougherty has been an extremely influential figure in his life.

"Dr. D is one of the best teachers I've ever had, including college professors," Subin says. "He shaped my education, from high school to college to law school. He was the guy I went to about everything, and I took every opportunity I could to hang out with him. I can't say enough good things about him."

Dougherty has since retired from full-time teaching, though he continues to substitute at O'Neal. He recently reprised his role at the NEH as a fellow at UNC's Center for the Study of the American South, coordinating filmmaking efforts and working with former NEH chair Bill Ferris.

He is currently working on two film projects at Chapel Hill, one about an African American choir called "Wings Over Jordan" and another about a newspaper editor in South Carolina who stood up to the Ku Klux Klan. He has also been named as a presidential counselor to the board of the World War II museum in New Orleans.

In his free time, Dougherty travels to France every summer to visit friends. He also makes frequent trips back to visit his elderly mother in Coaldale, where he often sees his friends from his childhood at the local bars.

It's been an amazing and interesting journey, one that Dougherty has no regrets about.

"I believe you have to give yourself completely to what you're doing," he says. "It's been a wonderful experience."

Source