James H. "Casey" Gildea was not the type to take everyday life as it came. No, not he. Skinny and balding, he was a scholarly kind who actively pursued all the avenues of his being. In his hometown of Coaldale, PA, locals described Gildea as "the man to look up to" and "the guy who always got the job done."

Such praise was warrented. Gildea was born for his community. Always modest and easily accessible, he walked down the same coal-begrimed streets everyday and loved every minute of it. Everyone greeted him. Conversations bloomed. He was involved in all the town's affairs. He combined generosity with straightforward cander. He was Coaldale's man of action.

Such praise was warrented. Gildea was born for his community. Always modest and easily accessible, he walked down the same coal-begrimed streets everyday and loved every minute of it. Everyone greeted him. Conversations bloomed. He was involved in all the town's affairs. He combined generosity with straightforward cander. He was Coaldale's man of action.

As the publisher of the Observer, Coaldale's daily newspaper, Gildea knew the whys, wherefores, and whereabouts of all the goings-on in the whole anthracite region.

Naturally, he was the leader in promoting local sports.

Shortly after World War I ended, a multitude of energetic young men found themselves back in the coal mines and missing the exhilaration they'd known in combat. Gildea believed that more fights could be fought on battlefields of a different kind. He sponsored, managed, promoted and supported many seasononal sports activities, including baseball and basketball teams. But, perhaps his greatest success came when a new sports frenzy took hold throughout the anthracite hills right after the war – pro football.

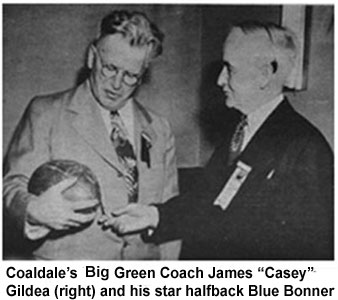

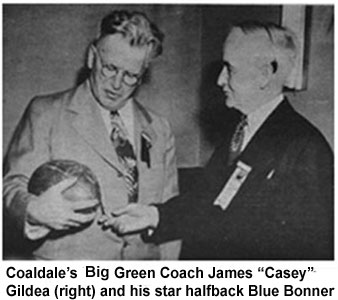

Coaldale's pro football team – the Big Green – was formed by Gildea, with a roster of mostly local talent. Nearby towns favored importing ringers for their teams, but Gildea preferred searching his own sector of the coal region for players. He came up with some gems.

Two of the best were James "Blue" Bonner and Jack "Honeyboy" Evans. Both were Coaldale natives, both were built like ironmen, and both could really punish Coaldale opponents.

Joe Devire, a journalist covering the Big Green in 1924, said of Bonner, "He is the most colorful player in independent football circles, built like a warrior, one of the most feared athletes on the gridiron. Bonner never went to a college, but he has played against stars of great colleges and has shown them things about football that they never knew existed."

According to Gildea, "Blue hit men so hard that they just didn't get up. He seldom used his hands to tackle, but used his hips and body, just like he blocked. When he ran the ball, his legs went up and down like pistons, almost touching his chin."

According to Gildea, "Blue hit men so hard that they just didn't get up. He seldom used his hands to tackle, but used his hips and body, just like he blocked. When he ran the ball, his legs went up and down like pistons, almost touching his chin."

Bonner wasn't a dirty ballplayer, Gildea insisted. He played within the boundaries of the rules, but he used intimidation as a weapon. Some referees believed he went too far and was indeed as dirty as the field he played on and tossed him out of games. Usually, whenever Bonner was absent from the lineup, the Big Green lost.

"I remember we went down to Atlantic City one year," said Gildea, "and their mayor issued an official proclamation barring `Blu' from entering the city on the day of the game. Boy, did we get a laugh out of that one."

One player on Gildea's squad who banished laughter from Coaldale's foes was Jack "Honeyboy" Evans. On the field, "Honeyboy" was anything but sweet.

"Jack was a very strong and very stubborn man," remembered Gildea. "Miners who worked with the big center recalled how he would draw together two loaded mine cars, his muscular arms like a giant vise, so the cars could be coupled."

Evans and Bonner were prime examples of Gildea's success in finding and winning with local talent. Les Asplundh, a former All-American punter out of Swarthmore College, was the exception.

"For weeks on end," Gildea recalled, "we had seen this fellow playing against us on several different teams. I guess you could call him a football gypsy because – as we later found out – he went from team to team, taking any offer that was better than the one he already had. He was such a good player that he was usually the deciding factor in many of our defeats. I decided that I had to do something about it."

Gildea met with the 6'3", 215 pound Asplundh and gave him a huge contract with bonus clauses.

Bill Dimmerling, a patriarch of the Pottsville club, one of Coaldale's fiercest rivals, lauded Asplundh: "He was a great kicker and punter. He could kick the ball a...mile. He was a big son of a bitch and he could kick like a bastard!"

Bonner, Evans, and Asplundh combined their unique talents to form the heart of one of the most successful teams in anthracite history. They coached themselves, copying plays and formations from other teams they'd played for or against.

Gildea explained: "I believed that with the kind of players we had on our roster that they should be able to compete without a designated coach. I handled all of the scheduling, recruitment, and details by myself. All they had to do was play the game ... and win."

The Coaldale Big Green did win indeed. They brought home three consecutive coal region championships in 1921, '22, and '23.

“Casey" Gildea went on to become a U.S. Congressman. At 97 he is believed to be the oldest living former member of that glorious legislative body. But his fondest memories?

"Boy! Those days with my team! That was the time to be alive. I've never forgotten the excitement of watching coal region football, the spectacle of it all. It was the greatest time for me."

Such praise was warrented. Gildea was born for his community. Always modest and easily accessible, he walked down the same coal-begrimed streets everyday and loved every minute of it. Everyone greeted him. Conversations bloomed. He was involved in all the town's affairs. He combined generosity with straightforward cander. He was Coaldale's man of action.

Such praise was warrented. Gildea was born for his community. Always modest and easily accessible, he walked down the same coal-begrimed streets everyday and loved every minute of it. Everyone greeted him. Conversations bloomed. He was involved in all the town's affairs. He combined generosity with straightforward cander. He was Coaldale's man of action. According to Gildea, "Blue hit men so hard that they just didn't get up. He seldom used his hands to tackle, but used his hips and body, just like he blocked. When he ran the ball, his legs went up and down like pistons, almost touching his chin."

According to Gildea, "Blue hit men so hard that they just didn't get up. He seldom used his hands to tackle, but used his hips and body, just like he blocked. When he ran the ball, his legs went up and down like pistons, almost touching his chin."